Known most famously for their mouth-watering fish tacos and tantalizing chili oil, Baja Bites has become quite a poppin lunch spot in La Ventana🤙🌶️🤤💥.

Paula and Alex, the owners, are both originally from different parts of Mexico and just like many of us, they met doing windsports in 1982 in Cancun. Quickly, they quickly fell in love and then with this town for its proximity to the outdoors. They now call this place home. Their favorite thing being that they can step out their front door to go biking and fishing. They are especially grateful for La Ventana’s chill vibe.

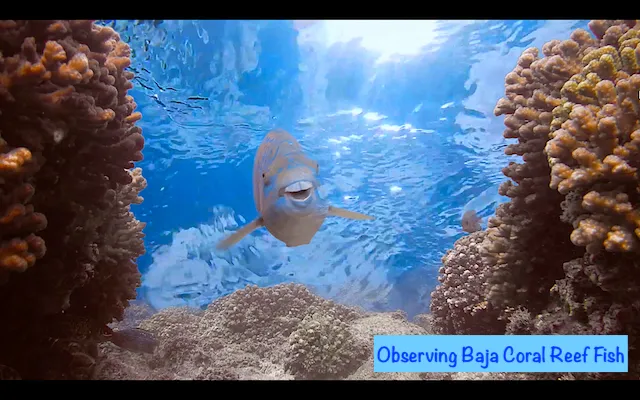

The two of them opened Baja Bites officially in 2017 out of a small trailer with a shark mouth painted on the front of it (see slide 4). You may remember that in the beginning there were just three taco options: yellowtail, shrimp, and marlin. Now, the menu features not only various taco options but also soups, salads, and baked goods. Although Alex can’t decide between the yellowtail or Tuna taco being his favorite item on the menu, he can confidently say that he is dedicated to serving good, fresh and local fish.

Come and see for yourselves! Make sure to bring along your pup and Alex will surprise them with a generous serving of fish. The Baja Bites team is always ready to greet you with a warm smile and excellent service!

⏰Open Mon – Sat, 11am-3:30pm

📍In El Teso next to KM0 & Diamanté reality.

📸 Crew pictured above left to right: Roman, Angel, Paula, Alex & Mona.