A Brief History

of the Founding of La Ventana

*****

Part 1

Pearl Explorers Who Visited La Ventana Bay

The Pericú women gathering seeds on a knoll above the shore stared in disbelief. A gigantic raft had just drifted into the bay. It made the balsas their men propelled with double-bladed paletas look like twigs floating in a tide pool. One woman sounded the alarm. [ balsas = rafts made by binding reeds or light tree trunks together, paletas = paddles ]

Pericú women sketched by George Shelvocke, an English privateer who visited the Cape Region during the early 18th century.

Fortún Ximénez, and his fellow mutineers dropped ancla in a large bay, and went a tierra in the mythical land of California, first imagined in a popular 16th century novel. They were the first Europeans to set foot on the Baja California peninsula. Some would be the first to die there. [ancla = anchor, a tierra = ashore]

The Spaniards came ashore to find water. When they saw the women, they knew una fuente would be nearby. The sailors whistled and joked as they approached the group who watched the extraños with apprehension. [ fuente = source, extraños = strangers ]

This will be más fácil than slitting Becerra’s throat and commandeering his ship, Fortún thought to himself. Cortés had sent Becerra to look for an expedition that had vanished without a trace. Fortún was an exceptional pilot, but he didn’t like taking orders. He preferred looking for the island of pearls described in the popular novel. For many Spaniards in 1533, that was evidencia enough that it existed. [ más fácil = easier, evidencia = evidence ]

The Pericú men appeared without warning. They seemed taller, and stronger than tribes on the mainland. For some reason they were angry. Arrows were already nocked in their bowstrings. But it was their black pearl-string necklaces that caused the sailors to miss the signal the Pericú leader gave to kill the crude intruders. Before Fortún could react, una flecha pierced his heart, and twenty of the crew would soon be muerto. The survivors escaped to the ship. They sailed home with tales of pearls that spawned new expeditions, some that would never be heard from again. [ flecha = arrow, muerto = dead ]

*****

Fortún and his crew’s deadly encounter with an indigenous Baja tribe, most likely self-inflicted, did not stop further exploration by Europeans. Instead, the lure of pearls would continue to influence the course of Baja history for the next 400 years. And that includes the founding of the pueblo of La Ventana.

Pericu stone tools from foothills above El Sargento (photo 2008)

*****

In 1535, Cortés led an expedition to establish a settlement on the bay where Fortún Ximénez had been killed . A chubasco blew his ship off rumbo, and a falling yard arm killed his pilot. Cortés took the helm and guided the ship through the darkness to an anchorage in the lee of an island. [ chubasco = violent and sometimes sudden summer storm, rumbo = course ]

At the first rays of alba, Cortés saw that they were anchored at the entrance to a large bay. He named it Bahía de San Felipe for the saint’s day that his buque/navio and crew found refuge from the storm. He named the island Santiago to honor the patron saint of Spain. Across the bay to the west, a narrow sandy belt was backed by steep mountains. They sailed north past a promontory, and followed the coast until they reached the bay they were seeking. There, Cortés established the short-lived pueblo of Santa Cruz, the first European settlement in Baja. [ alba = dawn, buque/navio = ship ]

Promontory Punta Gorda Seven Miles North of El Sargento

*****

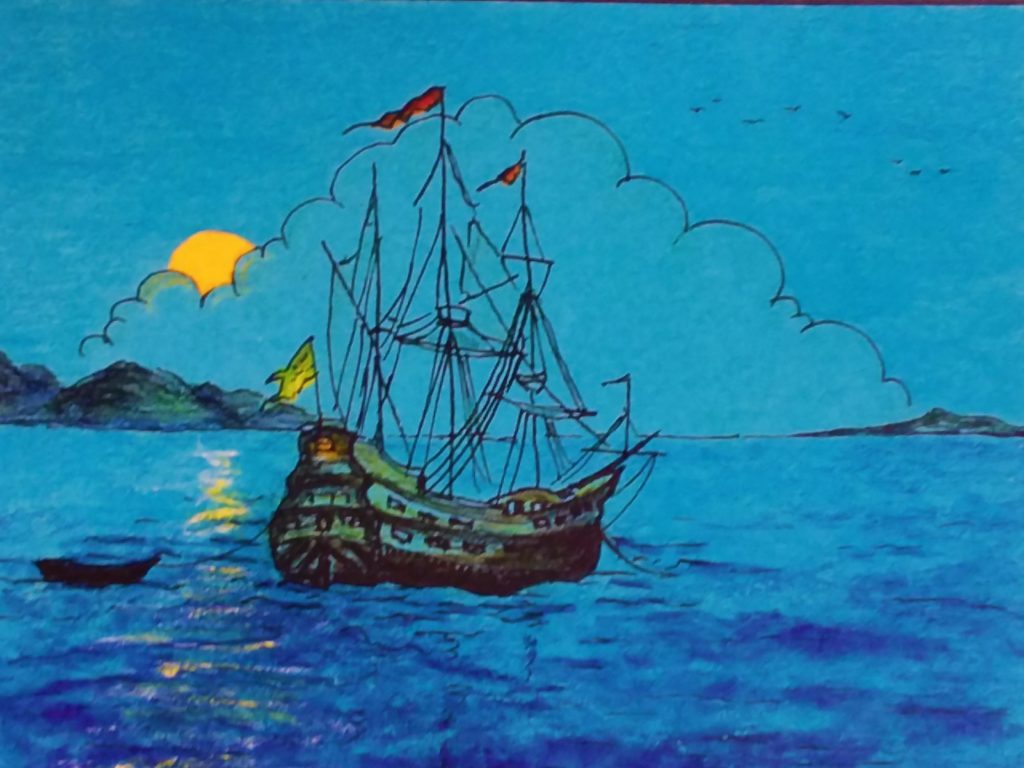

Sixty years later, Vizcaíno won a pearl fishing concession a explorar the western shore of the Gulf of California. He sailed out of Mazatlán on August 24, 1596, with three ships carrying horses, soldiers, women and children. They made the crossing in 10 days. The well-researched Cartografía y Crónicas de la Antigua California (León Portillo, 1985) pinpointed their landing site as “a bay that was baptized as San Felipe, la actual Bay of La Ventana.” [ a explorar = to explore, la actual = the current ]

Vizcaino and a squad of soldiers went ashore on September 3, and claimed the land for Spain, calling it Nuevo Andalucía. They were met by several hundred friendly Indians who traded pearls for knives and mirrors. They explored the surrounding region for a settlement site, but found the local population too barbarous to be converted.The expedition sailed north on September 10, and entered the bay of Santa Cruz. Because the Indians they met were peaceful, Vizcaino renamed the place La Paz. [ Indios amigables = friendly Indians, La Paz = Peace ]

After building a stockade, Vizcaino took 80 soldiers and sailed north for 10 days. Indians in five balsas met them and used signs to darles la bienvenida ashore. Vizcaino sent 25 soldiers ashore in the only landing boat they carried. When more armed Indians gathered on the beach, the boat ferried 25 more soldiers ashore. They followed the Indians to their watering source and ranchería where they exchanged gifts. [ darles la bienvenida = welcome them, ranchería = organized band of hunting-and-gathering Baja Indians occupying a seasonal settlement ]

All went well until a soldier struck an Indian in the chest with the butt of his harquebus. Vizcaino ordered a retreat and sent a boatload of soldiers to the ship while the others formed a rear guard. Five hundred Indians attacked. The noise-making harquebuses did not frighten the Indians until one was hit and fell bleeding to the ground.

When the boat picked up the shore detachment, the archers showered them with arrows, and the vessel capsized. In their heavy armaments, 19 drowned, and only 7 made it back back to the ship. Without a boat to go ashore, Vizcaino returned to La Paz. Another catástrofe struck when a viento fuerte blew sparks from a campfire that ignited a hut. Before they could extinguish the flames, the inferno destroyed half the structures and food supply. The second attempt to establish a settlement in Baja California failed. [ catástrofe = catastrophe, viento fuerte = strong wind ]

In 1683, indigenous tribes, who had made the region their home for almost 10,000 years, stopped two more attempts by Spain to colonize the peninsula. However, 12 years later, the Jesuit priest Salvatierra founded Baja’s first permanent Spanish settlement at Loreto. During the next 70 years, a total of 23 missions would be established by the Jesuits.

*****

Tom at

BajaNightSky@gmail.com

Next time

A diving bell deployed at Cerralvo? Baja’s first tycoon. Murder at Santa Ana.

Further Reading

León Portillo (1985) Cartografía y Crónicas de la Antigua California

Sands (2015) A Brief History of the Cape Region

Sands (2015) The Mystery of the Pericues

Shelvocke (1722) A Description of the Southernmost part of California, Pacific Adventures Number Two (1940)

#####

Part 2

A Diving Bell to Look for Pearls & Baja’s First Tycoon

A century after Cortés’ voyage, the 3rd Marquis of Cerralvo, Viceroy of New Spain, approved a permiso for Don Francisco de Ortega. Ortega had completed an apprenticeship for “Expert in Construction of Ships,” and was supervising preparations for an expedition. Friends provided financial backing for a share of the pearls and gold he found. In addition, Ortega had to pay the king his quinto de pearlas, report on potential settlement sites, and natural resources. [ permiso = permit, quinto de perlas = fifth of pearls ]

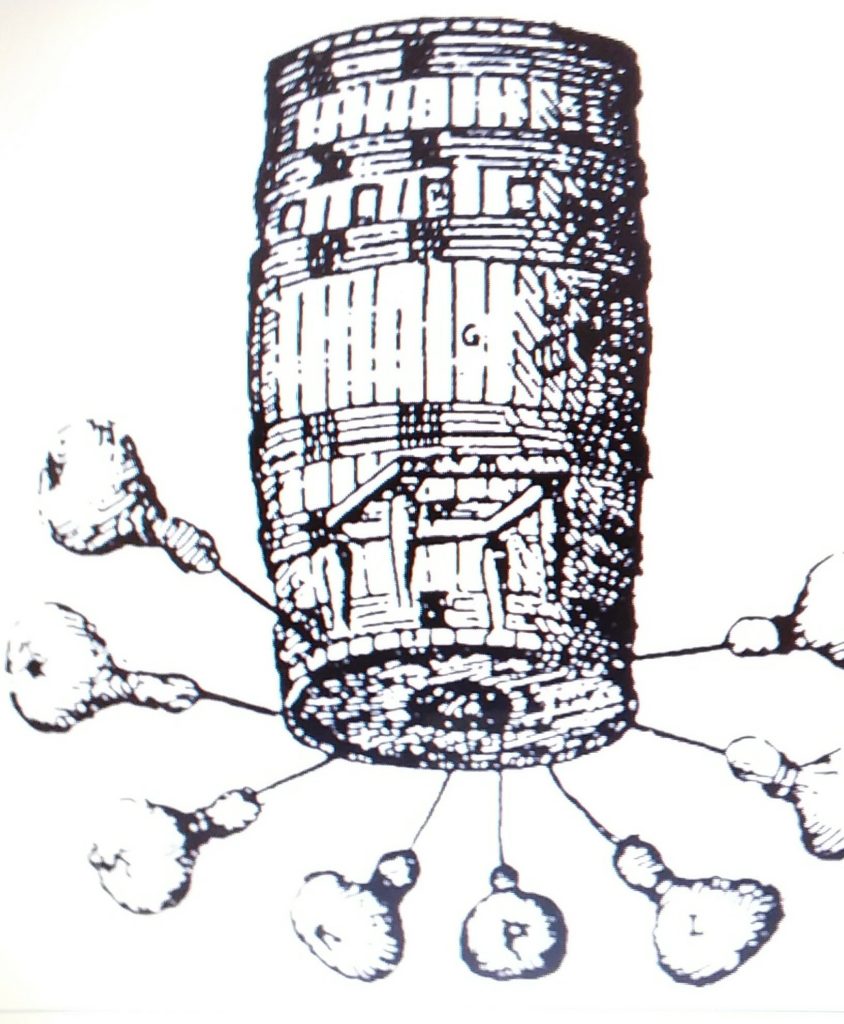

Ortega’s shipwrights built a diving bell from madera and lead. He claimed two men in the bell could safely gather conchas de perlas from the sea floor for several hours. The expedition launched the Madre Luisa in 1632. They crossed the gulf and anchored off Isla Santiago. Ortega took the bell on two more voyages, but never mentions if it was used. However, he did honor the Viceroy of New Spain by changing the name of Isla Santiago to Isla Cerralvo. [ madera = wood, conchas de perlas = pearl oyster shells ]

Ortega’s Diving Bell ( Library of Spain )

On Ortega’s third and last voyage, a chubasco slammed the ship onto the rocky shore of Cerralvo, smashing it to pieces. Everyone survived, but the disaster left them marooned. The crew retrieved the wreckage, and Ortega put them to work constructing another ship. Forty-six days later, navegaron north. Ortega discovered and named several more islands. He met with Guaycuras, and traded for pearls before sailing back to the mainland. [chubasco=storm navegaron = they sailed ]

*****

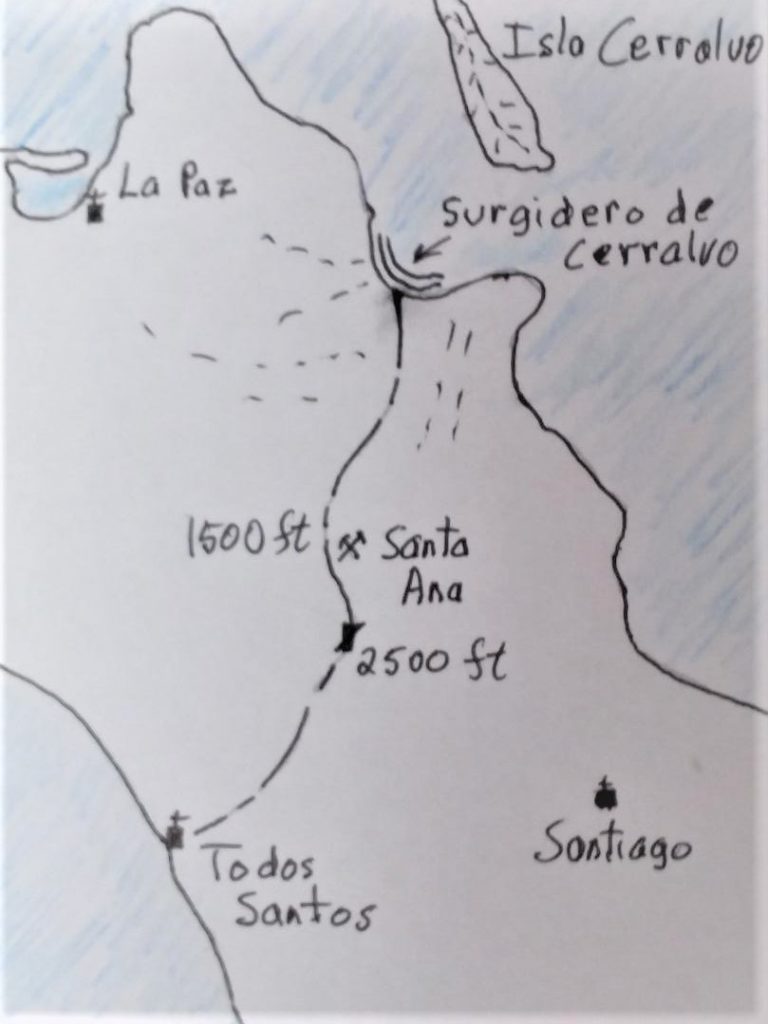

Manuel de Ocio, a soldier at the mission in Todos Santos, made a name for himself during the Pericú revolt of 1734. With another soldier and several friendly Indians, Ocio led Father Taraval on a daring nighttime escapada to Isla Espiritu Santo. Ocio had learned the lay of the land while picking up visitors and supplies at the Surgidero de Cerralvo, and escorting them back to Todos Santos. [Surgidero de Cerralvo = anchorage at SW corner of Ventana Bay, escapada = escape ]

Rebel Pericú converts had set up roadblocks on the route to La Paz. Ocio traveled at night on senderos that bypassed the blockade. At La Paz, they hid on the beach until friendly Indians brought them a sailing canoe. Ocio and the other soldier took Taraval to the the seguridad of Isla Espiritu Santo. The next day, they made their way to Loreto. Ocio subsequently married the daughter of the Presidio captain in Loreto, and was reassigned to San Ignacio. [ senderos = trails, = safety ]

*****

In 1741, on the gulf coast north of present day Santa Rosalia, a chubasco ripped thousands of pearl oysters from their beds, and tossed them onto the playas. Cochími converts knew that Misión soldiers accepted pearls in exchange for merchandise. They took los mejores they could find and went to Misión San Ignacio. [ playas = beaches, los mejores = the best ones ]

In 1697, Spain had rescinded all pearling permits, and the Jesuits took over governing the peninsula. They banned mission employees from pearling ventures. Ocio and other poachers did not let that stop them. He bargained with the Cochími for pearls, then resigned his position, and went to Guadalajara. El compró canoes, suministros to trade, hired divers, and headed back to the pearl beds. [El compró= He bought, suministros = supplies ]

After a few months, Ocio returned to Guadalajara and traded pearls for more canoes and supplies. He returned to Guadalajara after the próxima temporada with 275 pounds of pearls, causing a sensación that lured fortune seekers to the pearl grounds. Ocio returned there again with supplies that he sold out before the season ended. [ próxima temporada = next season, sensación = sensation ]

Ocio took his fortuna south, and built a cattle and minería de plata empire at Santa Ana, California’s oldest mine and first non-mission town. He was already familiar with the area, passing close to it when using the supply route from the Surgidero de Cerralvo to Todos Santos. When working fora short time collecting the quinto de perlas for the crown, he collected from divers working the bay. The waters around Cerralvo and the Surgidero were popular. Not only was there a fresh-water spring nearby, the pearl beds produced some of the best pearls found in Baja California. Ocio was murdered in 1771, by two miners while they robbed his storehouse. [fortuna = fortune, minería de plata = silver mining ]

Pearls turned Ocio into Baja’s first magnate. They also made Spain cauteloso of how the Jesuits were governing the peninsula. In 1768, seven decades after the priests had entered Baja, Carlos III expelled them. [ magnate = tycoon, cauteloso = wary/cautious ]

*****

Several decades after independence from Spain in 1821, the pearling industry took off. Armadores, the outfitters of the fishing fleets, sent armadas of ships to Bahía de La Ventana and nearby islands. Buzos in canoes spread out from mother ships to look for pearl oyster beds. [ armadores = outfitters, buzos = divers ]

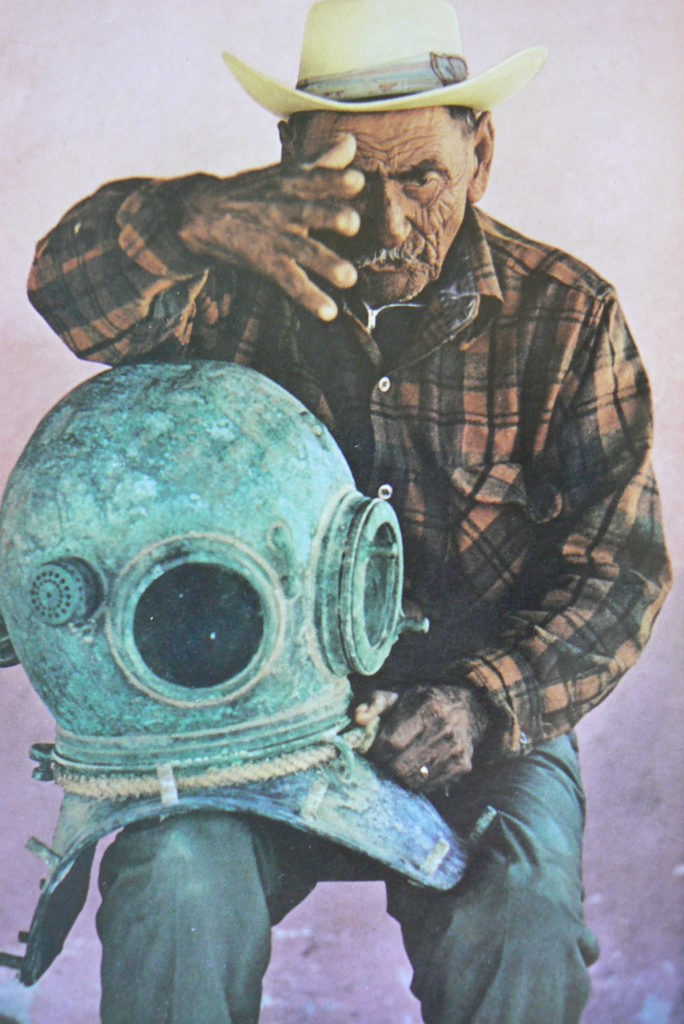

Change swept the industry in 1874, when two outfitters arrived in La Paz and introduced helmeted diving suits. Their divers could go deeper than free divers to harvest virgin oyster beds. The duo sold pearls for many times the cost of collecting them, and retired rich after one season. Other Armadores began importing diving gear. As a result, by 1910, La Paz became the pearling capital of el mundo, a busy, growing town of más que 9000 people. [ el mundo = the world, más que = more than ]

Tom at

BajaNightSky@gmail.com

*****

Next time

Pearl diver, Salomé León, establishes a fish camp that becomes the pueblo of La Ventana.

Further reading

Micheline Cariño and Mario Monteforte-Sanchez (1995), History of Pearling in La Paz Bay, Gems and Gemology

Cuclo, July 2018 Ortega’s Pearl Diving Bell

#####

A Brief History

of the Founding of La Ventana

by Tom Spradley

Part 3

Salomé

In 1910, Salomé León Lucero was 17 years old and recently married to Carlota Zazuetan. He had rasgos guapos, and the broad chest and brazos fuertes of a Yaqui Indian. Although his ancestry is not certain, one of his sons held this suspicion. Salomé and Carlota were expecting their first child. [ rasgos guapos = handsome features, brazos fuertes = strong arms ]

Salomé may have already saved a pequeña suma de dinero working for a pearling company such as La Compania Perlifera de Baja California in La Paz. Ideally, each small fishing boat they outfitted had to be equipped with an air pump, a buzo, two pump operators, and two remeros. [ pequeña suma de dinero = small sum of money, buzo = diver, remeros = rowers ]

A life-line man helped divers into their heavy diving suits, kept the air hoses untangled, and helped raise the buzo to the surface after a time that depended on the depth reached. In shallow waters, it could be an hour or more, but only a short time from sea floors too profoundo to be reached by buceo libre. [ buzo = diver, profoundo = deep, buceo libre = free diving ]

On shore, workers opened the mollusks a buscar pearls. Then they cleaned the mother-of-pearl shells, and sorted them for storage or export to Europe where craftsmen used them to make buttons, inlaid table tops, and other items. Mother-of-pearl soon brought in más dinero than the pearls themselves. [a buscar = to look for, más dinero = moremoney ]

Trabajar para a pearling company did not appeal to Salomé. He wanted to be an independent diver with his own diving gear. When his first son was born, Salomé dreamed about exploring for pearl’s with the boy at his side. He knew the risks. Buzos suffered from hearing loss, paralysis, and rheumatism due to sudden pressure and temperature changes. Sharks and mantas a veces attacked them. They died from equipment failures, accidents, or surfacing too quickly. However, Salomé loved the sea, and knew that every pearl he found would be his to sell. [ Trabajar para = Working for, a veces = sometimes ]

After acquiring un barco, and the necessary diving gear, Salomé worked as un buzo de perlas for almost 20 years. Of course, he rarely had the ideal crew of 6. More often it was just him and an assistant until a son was old enough to help. During the warmer months from June to October, Salomé explored the pearl beds around Isla Cerralvo, and the shoreline of Bahía de La Ventana. [ barco = boat, un buzo de perlas = a pearl diver ]

From time to time, they camped on sand dunes near the bufadora. Another diver had built a shelter there out of coral. During the evenings, divers relaxed around a hoguera de campamento to share stories about the day’s trabajo, their families back home, and rumors of newly discovered pearls beds. [ hoguera de campamento = campfire, trabajo = work ]

The oysters they dived for, Pteria Sterna, yielded pearls from about 3 of every 100 collected. But they might tener que abrir several hundred before finding one of any value. Divers dreamed of finding the one pearl that would bring them a small fortune. On one dive, Salomé brought up an oyster that yielded an excepcional green pearl. He sold it for a large bag of sugar, one of beans, a cow, and 1500 pesos, a small fortune for those days. Later, he heard that it had been sold to the Queen of Spain. True or not, traders did sell some of the best pearls from Baja to royalty throughout Europe. [tener que abrir = have to open, excepcional = exceptional ]

Around 1930, Sea of Cortés oysters began a morir from an unknown cause. Salomé was 37 years old, married to his fourth wife, and had 10 sons and 11 daughters. With prospects for finding pearls declining, he decided to go into fishing with his sons. He knew that the water between Cerralvo and the peninsula teemed with fish. They had camped in a palmar on the beach near the south end of the bay, a region then known as Miramar. It had access to La Paz through the mountains, or along the coast by canoe. He decided to establish a fishing camp there. [ a morir = to die, palmar = palm grove ]

When cooler weather arrived in 1931, Salomé and his family prepared for the journey to their new home. The arroyos near the palmar were probably dry so they would have to dig a pozo upon arriving at their destination. They must have loaded herramientas, fishing gear, food and water, and other supplies onto burros. And added a few goats and chickens to the caravan before setting out. They said adiós to friends, and to the cómodo hogar and prosperous town they were leaving behind. The trek through the unknown wilds of the Sierra de las Cacachilas was just ahead. The challenges of building a new life on the shore of Bahía de La Ventana was about to begin. [ pozo = well, herramientas = tools, cómodo hogar = comfortable home ]

*****

Why is the pueblo Salomé León founded called La Ventana? Local old timers suggest the name came from the narrow arroyo that passes the water desalination plant on its way to the beach. Trees arch over the arroyo’s terminus forming a window looking out to Cerralvo. This seems like a reasonable explanation until we learn that the bay was known as Bahía de La Ventana long before Salomé ever explored the area.

*****

Map #1 from 1826 shows Punta de Arenas and Anse de Cerralbo (Cerralvo Anchorage), but no La Ventana.

*****

Not until 1886, years before Salomé arrived on the scene, does Map #2 use Punta Arenas de La Ventana. So it appears that by 1886, La Ventana was the name given to the opening between Punta Montaña at the south end of Cerralvo and Punta Arena across the water. Together they created a ”Window” looking out on the Sea of Cortes that bestowed the same name on the bay. When Salomé and his family established their fish camp in the palmar, it was probably called La Ventana for the same reason.

#####

Tom at

BajaNightSky@gmail.com

References

Tom Spradley (2005), Interview with Josefa Amador Leon, Granddaughter of Salomé Leon

Tom Spradley (2005), Interview with __________ Leon, son of Salomé Leon, Ensenada