Pericu Indians

Time: 5,000 years ago. Location: Bufadora and Choco Lake area of present-day Bay of La Ventana. At dawn’s first light, the men started searching for shellfish in the shallows along the shore in front of the shell-midden dunes left by their ancestors. The women finished gathering acorns from the woodland where they had camped for the past moon. While they prepared the oak seeds for soaking to remove their bitter taste, they discussed moving camp to the base of the mountains where pitaya was ready to harvest.

A young girl approached the leader and asked her, “Where did our people come from?”

The old woman repeated the story she had learned from her mother: “Many winters ago, just before dawn on the shortest day of the season, Niparaya descended from the minyikári (sky) on the three stars that form the great hunter’s waist. He stood on Cerro Del Puerto, the sacred mountain to the west, and created all we need to survive. Pericú is the name he gave us. It means “The People.”

Strangers

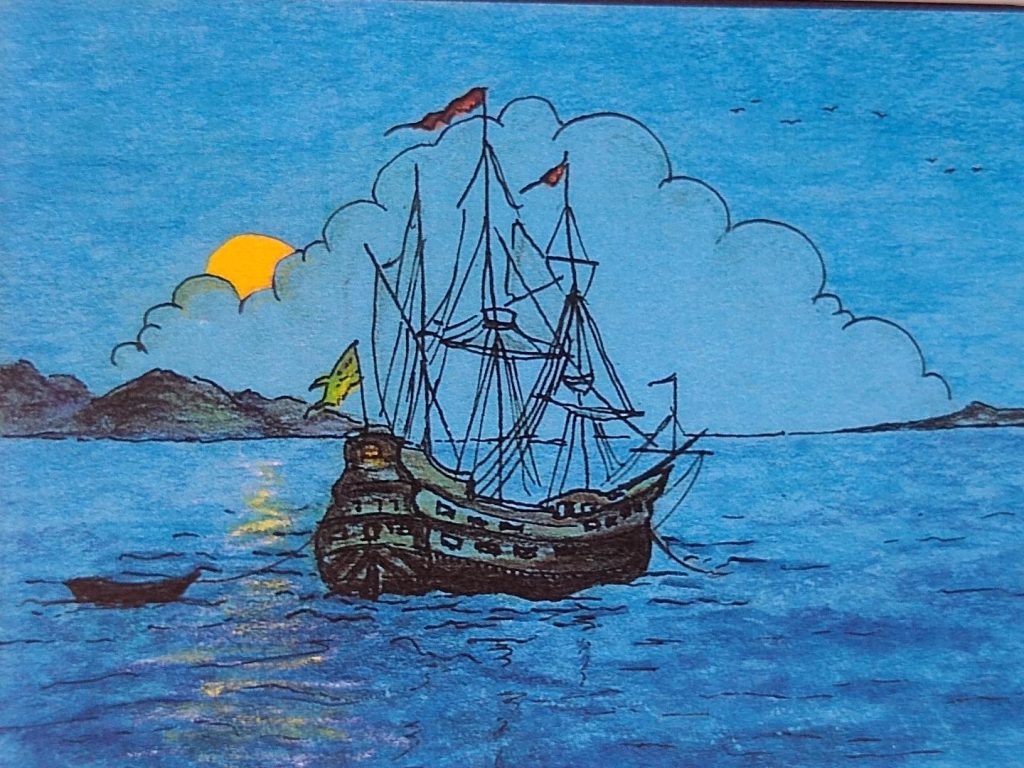

Time: 500 years ago. Location: a Pericú gathering place a day’s journey north of Hot Springs Beach. The Pericú girl gathering seeds and herbs on a knoll above the shore looked in disbelief. A gigantic raft had just drifted into the bay. The balsas the men propelled to the island with double-bladed paletas look like twigs floating in a tide pool next to this raft. She alerted the women.

Fortún Ximénez and his fellow mutineers went ashore. They were the first Europeans to set foot on the Baja California peninsula. Some would be the first to die. The Spaniards came ashore to find water. When they saw the women, they knew they would find a source nearby. The sailors whistled and joked as they approached the group.

Cortés had sent Becerra and Ximénez to look for an expedition that had vanished without a trace. Ximénez was an exceptional pilot, but he didn’t like taking orders. He preferred looking for the pearls described in the famous 1510 romance novel Las Sergas de Esplandián, about the mythical island of California. For many Spaniards in 1533, reading about an island in a book was all the evidence they needed that it existed.

The Pericú men appeared without warning. What they saw angered them, and they quickly nocked arrows in their bowstrings. The pearls around the indigenous men’s necks distracted the sailors. They missed the signal the Pericú leader gave to kill the crude intruders. Before Fortún could react, an arrow pierced his heart. He died along with twenty of his men. The survivors escaped to the ship and sailed home.

Fortún’s deadly encounter with the indigenous Pericu tribe did not stop further exploration by Europeans. Instead, the lure of pearls continued to influence the course of Baja California history for the next 400 years, including the founding of the pueblo of La Ventana by a pearl diver.

Hot Springs Beach

Time: 1535. Place: The Hot Springs Beach on Ventana Bay. Yrag whistled a rising chip chip chip, imitating one of the songs of the red bird that perched on a nearby cardón. It cocked its head, looked at Yrag, and flew just above the desert vegetation towards the mountains. Birds had sought shelter in the dense brush of the foothills for several days. Yrag and his small band of Pericu had enjoyed the beach’s abundant seafood and hot water bubbling up through the rocks, but Yrag knew birds sensed approaching storms hours before he did and decided to move camp. The band carried animal skins for warmth and bows and arrows for hunting and protection but left the metates and manos they used for grinding seeds. The warm bubbling waters, a gift from Niparaya, would always be theirs. And they kept heavier stone tools at the campsites they frequented.

Kcuhc and Ykceb led the group up a winding trail, crossed a sandy arroyo, and climbed to a cave where they took refuge. Yrag looked back at the island and did a double-take. He saw a huge raft with flapping white wings entering the bay at the island’s south end. We made the right decisión to move camp, he thought to himself. His grandfather had told stories about strangers who once came ashore from such a floating giant and threatened some of the women gathering food.

Aboard the ship anchored at the south end of the island, Cortes ordered one group of men to go ashore and look for freshwater; another group took the pilot’s body ashore and buried him. A yardarm, loosened by a storm, had fallen and killed him. Cortes christened the island Santiago, the patron saint of Spain.

The wind kicked up whitecaps as night fell and strengthened to a gale by dawn. After the storm, Kcuhc and Ykceb left to repair trails that led to water, shelters, rock workshops, and the sacred mountain. Their ancestors had used the pathways for centuries to spread news, visit relatives in other Pericu bands, and attend ceremonies. Evets and Onnamre had trained to run these trails through the Cunimniici (Pericu word for mountain range) when vital information needed to be shared quickly. They left to carry news of the strangers to other Pericu bands.

Viscaino Visits the Bay and Attempts to Settle “New Andalucia”

On September 3, 1596, Vizcaino entered a large bay in Baja, California, with three ships carrying horses, soldiers, women, and children. He named the bay San Felipe (the current Bay of La Ventana, León Portillo, 1985).

When Vizcaino and a squad of soldiers went ashore, several hundred friendly natives met them and traded pearls for knives and mirrors. A presumptuous Vizcaino claimed the Pericues’ land for Spain, calling it New Andalucía, and ordered the construction of a settlement. But the foreigners quickly found the local population too dangerous to settle near and sailed north on September 10 to the bay of Santa Cruz. Because the Indians there were peaceful, Vizcaino renamed it La Paz

Francisco de Ortega Explores for Pearls

Almost a century later, Martín de Lezama, son-in-law of Vizcaino, wanted to try his luck in California. The 3rd Marquis of Cerralvo, Viceroy of New Spain, approved a permit for Lezama. Explorers had to build their ships, so Ledsema took sailors, carpenters, and tools from the Gulf of Mexico, across tropical jungles, to a port on the Pacific coast. He found the “inhospitable land and the many mosquitoes” not to his liking and soon abandoned the project, leaving everyone else stranded.

The hostile environment did not deter Francisco de Ortega. He had completed an apprenticeship for Expert in Construction of Ships. It took him four years to raise funds, build a frigate, and negotiate permission from the Viceroy to embark on a voyage of discovery and mapping of Baja California. All explorers had to pay the king a quinto de pearlas – a fifth of the pearls they found.

The expedition launched the Madre Luisa in 1632. They crossed the Gulf and anchored off the island that Cortés had named Santiago. Ortega honored the Viceroy of New Spain by renaming the island Cerralvo. They explored and mapped the pearl beds on the bay’s shores before returning to the mainland.

The crew of the Madre Luisa launched Ortega’s third voyage on January 11, 1636, and favorable winds carried them across the Gulf in two days. They entered present-day Ventana Bay on the afternoon of the 13th and sailed up the coast, anchoring for the night opposite Cerralvo’s north end. At dusk, the wind began to blow.

The following day calamity struck. The ship’s scribe recorded that “a cable broke and dragged the anchor, the wind and waves increased so that we were hurled against the shore where the frigate broke up.” Everyone survived, but the disaster left them stranded. The crew retrieved planks from the wreckage and built another ship. The new but smaller boat was the first sailing vessel built in the Californias. Forty-six days after the storm had destroyed the frigate, Ortega sailed into La Paz Bay, where the native Indians welcomed them. After replenishing their water and firewood, the explorers left the bay and anchored near Cerralvo. Divers assessed the extent of the pearl beds, and the captain later describes this in his report. They sailed north, and Ortega discovered and named several more islands. He met with Guaycuras and traded for pearls before sailing back to the mainland.

Tax Collector Manuel de Ocio Comes to Ventana Bay

Manuel de Ocio trained in Spain to work as a blacksmith. Seeking adventure, he traveled to Baja, California, and served as a soldier at Mission Todos Santos. He often rode over the Peninsular Divide to the Surgidero de Cerralvo, an anchorage at the SW corner of Ventana Bay, to pick up visitors and supplies from ships anchored there. During these trips, he came within a few hundred feet of where he would open the peninsula’s first silver mine and establish Santa Ana, its first secular town.

At the start of the Pericú revolt of 1734, insurgent Indians murdered two priests at Santiago and headed to Mission Todos Santos to capture Father Taraval. Rebel Pericú had set up roadblocks on the route from Todos Santos to La Paz to prevent mission personnel from escaping to the mission to the north. With another soldier and several friendly Indians, Ocio helped Father Taraval escape, traveling at night on trails he knew bypassed the blockade. At La Paz, they hid on the beach until friendly Indians brought them a sailing canoe. The two soldiers took Taraval to the security ofIsla Espiritu Santo. The next day, the group made their way to Loreto. Ocio subsequently married the daughter of the Presidio captain in Loreto and later was assigned to San Ignacio.

In 1741, on the gulf coast north of present-day Santa Rosalia, a storm ripped thousands of pearl oysters from the ocean floor and tossed them onto the playas. Cochími converts took the best pearls they could find to Misión San Ignacio to trade for merchandise. Ocio bargained with the Cochími for pearls, then resigned from his mission job and went to Guadalajara. He bought canoes, hired divers, and headed back to the pearl beds. He returned to Guadalajara several times to trade pearls for supplies and bank more profits. When new fortune seekers headed for the pearl grounds, Ocio followed them with supplies they would need and sold out before the season ended. Knowing that the newcomers were required to pay the king his quinto de perlas, he bought the rights to collect it. The fee he paid the crown allowed him to keep all the quinto de perlas he could collect from divers.

Ocio collected the pearl tax along the coast down to the Surgidero de Cerralvo, a popular location. Many of the best pearls taken from the Sea of Cortés came from Ventana Bay. And there was a source of fresh water not far from the dunes where divers set up camps for the season.

Ocio used his fortune to build a cattle and silver-mining empire at Santa Ana (ruins are near San Antonio), California’s oldest mine and first non-mission town. He brought laborers from the mainland, paid them little, and did not allow them to return home. His greed would prove to be his downfall. His wealth, among other things, made Spain suspicious of the Jesuits. In 1768, seven decades after Jesuit priests arrived to convert Indians on the peninsula, Carlos III expelled them. In 1771, when Ocio caught two employees robbing his storehouse, they attacked and killed him.

The Transit of Venus

Ventana Bay played a minor role in the first worldwide multinational scientific project. In 1769, the Mexican polymath Joaquin Velázquez de León disembarked with others from a ship anchored at the Surgidero de Cerralvo. The Viceroy sent Velázquez to study the region’s mining resources, report on its economic potential, and time the transit of Venus across the face of the sun. This event only happens twice a century; the most recent transit was in 2012. Other European scientists visited widespread locations to time the event from those places. Velazquez set up his observatory on a hill near Santa Ana and obtained accurate data about the transit. He computed the distance to the sun from the combined worldwide observations, which was impossible until then. He also found that the longitude for the Surgidero de Cerralvo was incorrect by almost two miles.

Next time we will meet Salome Leon, pearl diver and co-founder of La Ventana.