Part 2 — The First Settlers

Salomé’s caravan made its way over the dusty trail from La Paz to the palm grove on the Bahia de La Ventana, stopping to camp one night in the mountains. Salomé later commented that he was so weary by the journey’s end that even the hat on his head was too much weight to bear.

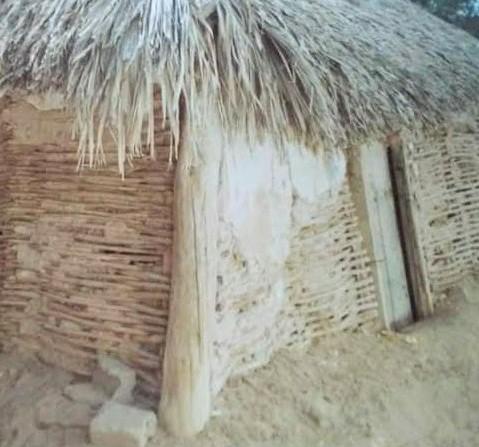

Salomé and his sons scoured the surrounding desert for palo de arco and downed cardón trunks to build a shelter. They chose a construction site under a stand of palm trees on the north side of the palmar overlooking the bay and Isla Cerralvo. They used the cardón for the corner posts and roof beams, wove the palo-de-arco walls and plastered them with mud. Then they attached layers of palm fronds to the roof and left the dirt floor bare. This type of shelter, called a jacal, was standard in many rural communities of Mexico in those times.

The home was illuminated with oil lamps and candles, and Salome furnished it with a table, chairs, and beds of cardón cactus tied together with palm rope. A blanket separated the interior into two rooms. Salome’s second wife, Petra, cooked on a metal grate over a wood fire. A typical meal consisted of beans, rice, corn tortillas, and fish. After the men brought goats back from the Island, meals included cheese and meat. The children collected wild fruit and herbs from the desert.

Rosendo Amador, who had herded cattle at Punta Perico with his son Jesus, had already brought his family to the palmar and built their jacal at the south end, where he also dug a well. The two pioneer families relied on each other for survival. The marriage between Jesus Amador Hiraldo and María Teresa León Zazueta, the children of Rosendo and Salomé, would seal the close bond between the two families.

***

Josefa Amador León was born on November 22, 1948, in her parent’s jacal in the pueblo of La Ventana. A barn owl kept watch from the tallest palm tree near the house. Josefa’s uncle and her maternal grandfather, the pearl diver Salomé León lived in the adjacent home.

“My maternal great grandparents settled in Rancho el Carmen near Los Planes in the mid-1800s,” Josepha recalls. “Salomé was born about 1893. He married the first of his four wives, Carlota Zazueta, while still a teenager. They had five children, Salomé, Teneza, Jesus, Enrique, and Ruben. Only Ruben survived until recently; he died in 2014. Five of Reuben’s children still live in the area. Joaquin is the owner of Rincon de la Bahía, a popular La Ventana restaurant just north of the campground. Raúl is the owner of a La Ventana market. Javier operates a tire shop in La Ventana. Salomé married two more times and had 16 more children, including my mother. All the sons of Salomé worked as fishermen except for one.”

Jesus Amador, Josefa’s father, built the village primary school ramada (shade structure) from palm branches to shelter the students from the intense tropical sun. It was located under a giant mesquite tree at the south end of the palmar near the village well.

“I attended our palapa school through 4th grade,” Josefa recalls. “There were only a few students, but we all learned to read, write and do calculations with the help of our teacher Graciela. After class, we had to gather firewood, milk the cows and goats, haul water from the well and pick edible plants from the desert as they ripened. When someone yelled pez (fish), we ran for the surf. Schools of jurel (mackerel) sometimes came right up in the shallow water after riding a breaking wave. Often there were so many fish in the surf they were all you could see. You just grabbed them by their tail and ran for shore. We learned to swim by the time we were three years old and had no fear of entering a crashing wave to grab a fish.

“In the early summer months, the mangoes ripened in the Arroyo de León, the deep canyon you see looking to your right at the top of the long grade on the road to La Paz. The man who planted the orchard built the old house you see there. He moved on, but there was usually enough water from a spring to produce a good crop of mangoes every summer.

“There is a trail from La Ventana up to the orchard. Several of us used to take bags and a donkey or two and leave early in the morning on the three-hour hike to pick mangoes. Sometimes we also hiked to the waterfall farther up the arroyo. When Rock Nettle was in bloom, Xantus’ hummingbirds usually fed on their yellow flowers. After loading the sacks with mangoes, we returned home to enjoy them with our families.

“Salomé and his sons made trips to La Paz on foot with a donkey or sometimes by canoe to buy food and other necessities. It was a special treat when they returned with fresh fruit and vegetables. They also made trips to San Antonio to buy beans, rice, and masa to make tortillas. Fishing was excellent, so they used their catch to barter for food and other items. Raymundo opened the first store in El Sargento, where Tani’s damaged welding shop now stands. Raymundo was the brother of Victoriano, who we met in the chapter about El Sargento. He raised Tani when the latter’s parents died. We walked for an hour each way through the desert to buy food at Raymundo’s store. There was no road between the towns until around 1975.”

Josefa’s father, Jesus Amador, was the first delegate from La Ventana to La Paz. He walked to all the meetings, whether in La Paz or San Antonio and sometimes spent a night in the Sierra. He had a rapid stride that took him long distances without stopping to rest. The trail to La Paz began in the gap through the mountains across from the trailer park. When there was a birth, death, or marriage in the village, he got up early and walked to San Antonio, almost 20 miles away, made his report, and returned on the same day.

Josefa will never forget the hurricane that struck La Ventana in the fall of 1958.

“It hit during the early-morning darkness before we had time to head for higher ground. A tromba marina (waterspout) that came ashore caused the worst damage. It brought in a big tide and dumped vast amounts of water on the hillside that flooded our houses and caused a landslide that partly buried my grandfather Salomé’s Buick. I remember standing on my bed as water and small fish and rays swirled around inside the house. After the water receded, everyone agreed it was time to move to higher ground and build more substantial houses.”

People lived on a ranch in the Las Canoas Arroyo for many years, back in the mountains above La Ventana, raising cattle and working gold mines. Occasionally, Josefa and her friends hiked up the arroyo to the ranch. When the children living there saw them approaching, they would run and hide. They were shy and never spoke to anyone from the outside.

“My father told me a story about what happened when he first moved to La Ventana from Punta Perico, where he and his father had taken care of cattle,” Josefa recalls.

“On moonless nights, a girl from the mountains used to come down to see Jesus. She would whistle when she arrived at the edge of the village, and he would go out to see her. They met each other regularly like this for some time. As a young boy, I think my father was quite enamored with this secret night-time liaison. Then one day, the girl came down during the day to see him. She turned out not to be as attractive as my father had imagined in the dark. After that, he never went out at night to meet her again.

“My father became a good friend of Agustin Lucero, who lived in La Ventana. They met on Cerralvo while fishing. They loved to sing out on the Island with Agustin playing the guitar.

“In 1962, when I was 14, my brothers met Guillermo on the Island and invited him to come and meet our family. He was probably their first friend from outside our village. I think he came to visit to meet me. I was milking a cow when he showed up. He found a glass and handed it to me, and asked if I would fill it directly from the cow for him. I told him to sit down and fill it for himself. Guillermo squeezed and pulled on the cow’s teats but could not get a drop of milk. When he gave up, I sat down and told him to come close and watch exactly how I did it. When he had his face near the udder, I started milking but turned one teat so that a stream of warm milk splashed him in the face. Then I just laughed and laughed and continued milking. Guillermo was quite surprised and a little embarrassed. However, it was love at first splat.

“After that, Guillermo came around more often. Sometimes he stayed over when he visited my brothers. We became fond of each other. As more people came to La Ventana, some would host a Saturday night dance on their property with someone to play the guitar or a victrola. If the dance was in Los Planes, a band called Los Osunas played. Guillermo usually came. He complained he had a long walk to return home in El Sargento after the dance, so he offered to walk me back to my house before the fiesta had finished. After Guillermo told me goodnight, I found out that he had returned to the party to dance with the other girls. To this day, I don’t know if he also walked them home! After discovering what he was up to, I never let him walk me home again until the dancing was over.

“If Guillllermo wanted to come over to see me and didn’t want the rest of my family to know, he would hide a short distance from the house and whistle chi-cá-go, chi-cá-go, chi-cá-go, like a codorniz (quail). I would find an excuse to look for something and go out and meet him. In 1972, ten years after we first met, we got married. Guillermo and I shared a small jacal with my sister and her husband, Pelon. My father lived in a cardboard and palm jacal, larger than the earlier ones in the campground.

Ana León remembers that her father was only 4-5 years old when her abuelo (grandfather) Salomé went pearl diving to distant places such as Veracruz, Manzanillo, and San Blas. “They took two boats, one for the machinery and one for the crew. On one of these trips, he was injured while working on the Eureca, the boat carrying the machinery.

“At the age of twelve, I went to study in La Paz. When I returned the next year, after a hurricane had destroyed all the houses, everyone had moved to higher ground to build new homes. But that old village in the palmar is still clear in my memory.”

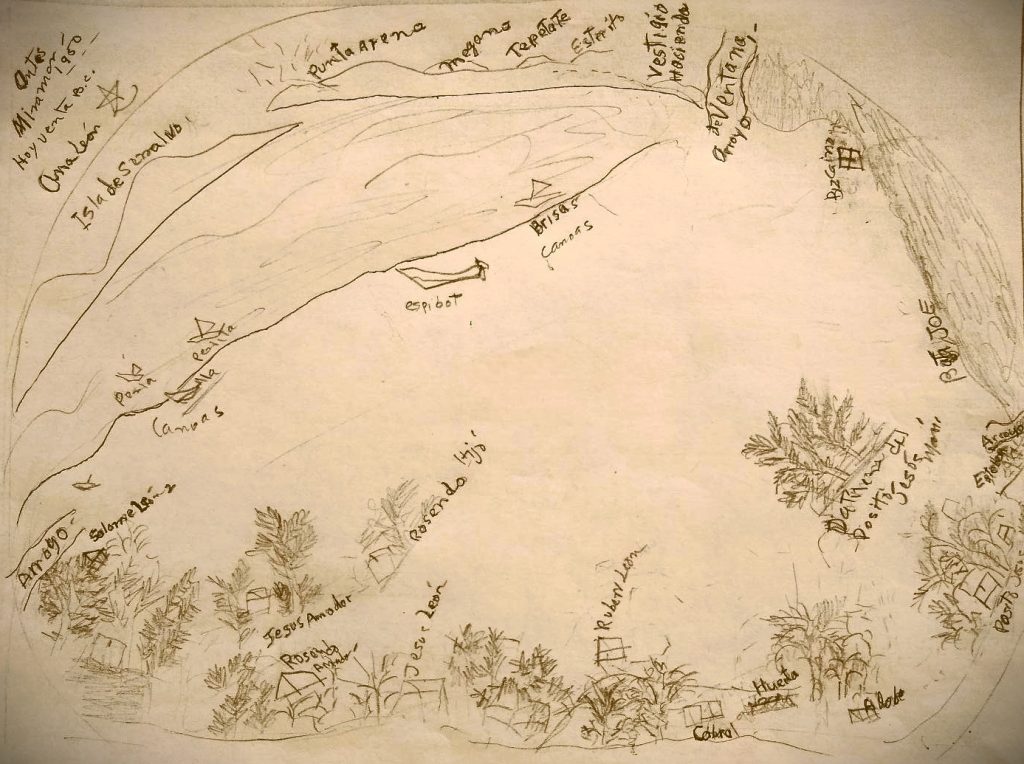

Ana Leon sketched this map of the bay and pueblo of La Ventana in the campground.

Pilar León was a young teenager when she came to live with us (author and wife Louise) in Sacramento, California, in 2006. She wanted to improve her English and return to Baja to work in the tourist industry. Now Pilar helps operate Baja Joe’s. She interviewed her mother, Carlota León Lucero, in 2009 and shared what she learned with me. Carlota is the daughter of Enrique León Zazueta and Pilar Lucero Barrera. Enrique was one of the sons of Salome. Enrique and Pilar came to La Ventana in 1948 when only three families lived here, those of Salome León, Rosendo Amador, and Geraldo Aviles.

Carlota was born in La Paz in 1950 and grew up there and in La Ventana.

“I attended the first and second grade in La Paz and the third in the El Sargento,” Carlota recalled. “School in El Sargento was difficult because usually there was no teacher. It was a four-hour drive from La Paz to La Ventana over dangerous, unpaved roads for many years. Not many teachers wanted to take a job in such a remote place. I had to help in the kitchen at home, which was not an easy job because we had to cook everything over a wood fire. I cleaned the house very early and then helped prepare breakfast for the men. The fishermen in the family always ate first, then the women.

“It was not the custom to celebrate Christmas with gifts. My mother sometimes cooked the family a special meal such as a soufflé or fritters. Very rarely did we exchange gifts. We did celebrate the day of the Virgin Mary. We would gather at a neighbor’s house to dance and eat delicious food on these occasions.

“We used to have fun sliding down a dune on giant turtle shells. We chose the biggest shell we could find left by fishermen on the sand. We’d put salt on the shells and dry them in the sun to make the surface slippery. Then we carried them up the dune and slid back down.

By chance or good luck, someone discovered a deposit of black stones in the La Ventana arroyo with the window formed by arching trees on each bank. They polished the stones until they looked like black pearls and sold them in La Paz.

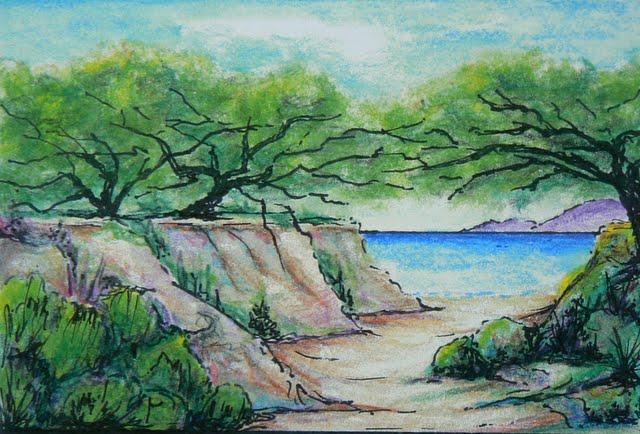

Sketch by Louise Spradley

“My uncle, Sr. Rubén León, bought a battery-powered TV around 1962. Every afternoon, neighbors met in his house to enjoy watching TV.”

“The Ruffo brothers had a ranch on Cerralvo Island that was cared for by my other grandfather, don Juanito Lucero. He brought supplies to the Island from La Paz in a small sailboat called a chalupine. To get to the Island, Don Juanito weighed anchor in La Paz and set sail to the north, then east and south to the ranch about midway along the west coast of Cerralvo, a distance of some 50 miles. With contrary winds, the voyage could take an entire day. Most of the cattle raised there were slaughtered and sold to pearl divers or markets in La Paz. Some of the goats escaped and multiplied. Today there are hundreds of wild goats on the Island.

Around 1986, John and Gail Chestnut flew into La Paz. After exploring the town, they rented a car and drove over the new road to Los Planes. On the return trip, they followed the dirt road into La Ventana.

“I think John and Gail were the first foreigners to build a house in La Ventana,” Josefa recalls. They drove past our houses to the arroyo just north of the campground and set up a tent. There was no one living between La Ventana and El Sargento yet. The campground area was not fenced, and cows splashed in the water near the palm trees. The men kept their pangas on the beach there. John and Gail returned two years later and bought property across from the campground. They got a rancher, Marcelo, to build a cement block house for them and then oversaw the building of our new home next door.”

A few years later, while building a wall for Baja Joe, Guillermo met Bruce of Sheldon Sails – the first person to kitesurf on the bay. The only Spanish Bruce knew was, “Como se dice este?” How do you say this? Bruce got Guillermo’s attention and pointed to a bald tire on his Chevy Suburban and asked, “Como se dice este?” Guillermo always has a good laugh about what happened next. He told Bruce, “llanta.” For the next few hours, Guillermo could hear Bruce saying to himself, “llanta, lanta,….. llanto… damn.” Then he would ask Guillermo again and walk away, repeating, “llanta, llanta, llanta.” It took him all day to learn that one word. However, when Bruce started having a beer after work with Guillermo, his son Jamie, and friends Pelon and Raul, he started speaking Spanish like a La Ventana Mexican in a short time.

Guillermo stopped working as a fisherman around the time Steven started Ventana Windsurf, possibly in 1996 or 1997, and was offered jobs as jardinero (gardener) by several people living nearby.

“Sometimes, I miss our life forty years ago,” Josefa told me. “Of course, we had less variety of food, no electricity or other modern conveniences. However, it was very peaceful and quiet. There was no crime and very little sickness. Life was slow-paced. The sky at night was aglow with an unbelievable number of stars. There was more physical work, like hauling up water and milking the cows and goats. But I loved it.”

Author note: My wife and I visited our El Sargento property in 1998. Guillermo was my first Spanish teacher. When he helped me pull out plants to make room for Marcelo to build our home, he taught me the word for “root.” I spent the rest of the day working and repeating to myself, raíz, raíz, raíz, rice, damn. We returned home, and I immediately signed up for a Spanish class.