Introduction

In Part 1 (see Part 1 here), Cortés landed on Cerralvo, and named the island Santiago. Vizcaino tried to found a settlement here. Now, a century later, we meet Francisco de Ortega who visited our bay three times. Evidence suggests he landed here, befriended the Indians, and reported on their customs. An ingenious and politically astute person, he carried a new machine to aid in the search for pearls. Ortega and crew were marooned when their ship broke to pieces on the rocks north of Punta Gorda.

Part 2 — The Voyages of Francisco de Ortega to La Ventana Bay 1632-1636

Kcuhc and Ykceb left camp at dawn. They had work to do on a trail to Cerro del Puerto (Pericú sacred mountain west of El Sargento). They hiked up a narrow arroyo past red-billed colibrís (hummingbirds) feeding on the blossoms of a plant hanging from the arroyo’s south wall. On the opposite side, abejas (bees) worked on honeycomb inside a rock alcove.

At a mojón de roca (rock cairn), the trailblazers climbed to a ridge where a giant, old, gray-top cactus stood. Its multitude of tall columns towered high above their heads. They had used rebanadas (slices) cut from young gray-tops to treat stingray wounds. But the tribe was in awe of this old gray-top. It was one of several natural landmarks created by Niparaja throughout the Cunimniici (Pericú word for mountain range, the Cacachilas and others of Baja Sur) to guide them to water, shelters, and sacred sites. The ancestors had left other landmarks on the sides of giant boulders: images of animals, humans, hands, and geometric figures.

*****

A century after Cortés’ voyage to the Baja peninsula, Martín de Lezama, an accountant in Mexico City, and son-in-law of Vizcaíno, wanted to try his suerte (luck) in California. After the Viceroy of New Spain, the 3rd Marquis of Cerralvo, approved his plans, Lezama hired carpenters and shipwrights, and took everyone to a place on the Pacific coast with good access to timber to build his ship. However, after the Crown ordered the Viceroy to halt further exploration of California until he could determine if colonization was advisable, Lezama found “the inhospitable land and the many mosquitoes,” not to his liking. He abandoned the project, and returned, leaving everyone else stranded.

Francisco de Ortega, who had completed an apprenticeship for Experto en Construcción de Naves (Expert in Construction of Ships) was not deterred by picaduras de mosquitos/zancudos (mosquito bites) or official decrees. He raised funds and completed Lezama’s frigate. Then he suggested to Viceroy Cerralvo that, at his own expense, he could embark on a voyage to provide him with the information the Crown desired. The Viceroy went for the idea and issued a permit that stated Ortega should “… discover ports and inlets of islands and coasts … record where it is possible to cast anchor … inform himself with respect to what natives inhabit that land, their customs … without offending or mistreating them, proffering all the kindness and attention possible … fish for pearls, and authenticate it all under oath with the testimony of a scribe.”

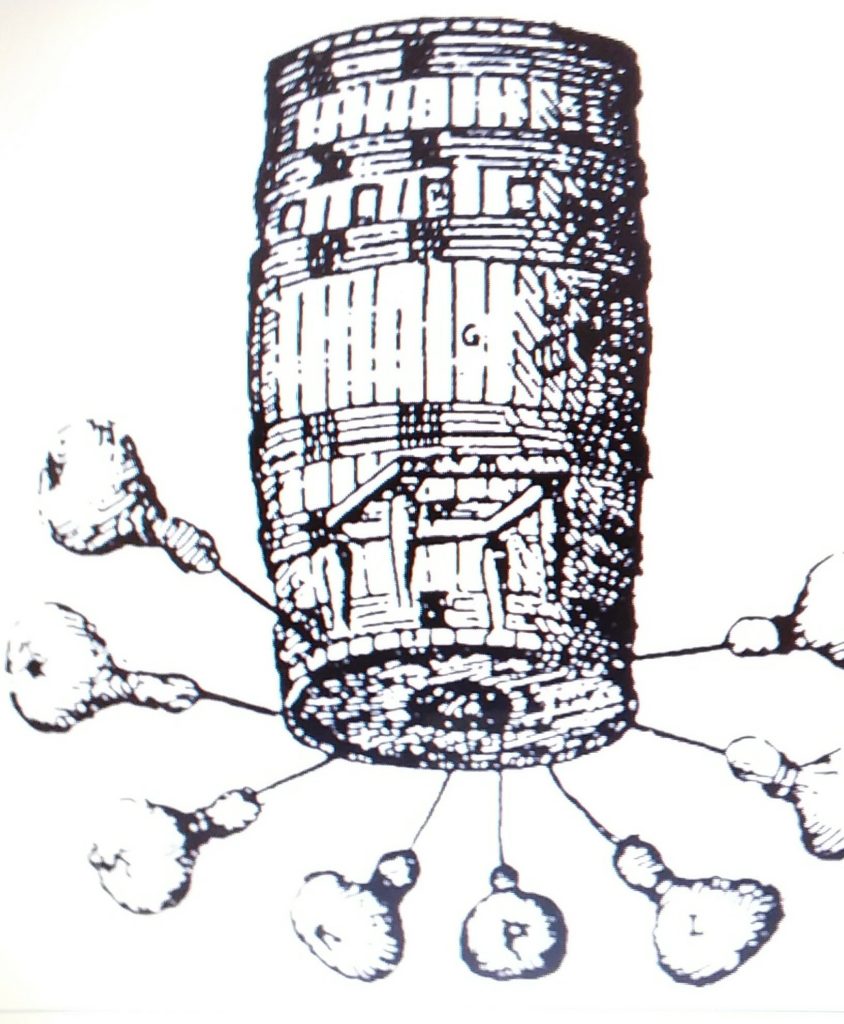

The government’s inspector reported that the frigate was in excellent condition, recently cleaned, well caulked, its sails new, adequate rigging, and two new anchors. He also stated the ship carried a new invention of Captain Ortega, “a bell of madera (wood) and lead, so that two persons can enter it and go down to whatever depth without danger of being drowned even if they remain under the water for ten or twelve days.” An account by Esteban Carbonel, Ortega’s pilot, is more specific about Ortega’s invention, stating that “… with machines and divers he had, he would collect a great quantity of pearls.” It was not unusual for Baja California explorers to exaggerate to obtain a permit or enhance their discoveries. According to one, there is a navigable river just north of Punta Gorda.

The expedition’s official certificate listed a tripulación (crew)of 22 consisting of a priest, ship’s master, assistant pilot with diving experience, boatswain, scribe, sailors, soldiers, ship’s boys who waited on all the others, an Angolan slave, and two mulatto women who attended the priest and Ortega. One of the ship’s boys was a barber and surgeon.

The Madre Luisa sailed north on February 11, 1632, but a storm forced Ortega to seek refuge at Mazatlan. They stayed for two months to make revisions and gave the local parish some of the cargo to lighten their load. In return, the local priest prevented several of the crew from jumping ship by coming aboard to “… give talks and encouraged them to go on said journey, helping the Captain to calm some who had changed their minds about the undertaking.”

With the crew encouraged and the ship provisioned, they set sail across the Gulf on May 1. The voyage sometimes takes several weeks, but with favorable winds they made the crossing and anchored off Isla Santiago on May 3, El Dia de La Cruz (The Day of the Cross). During the ship’s first watch that night, the sparkling stars of La Cruz de Mayo (The Cross of May, or Southern Cross), stood just above the mountains to the south of their anchorage. A full moon was rising in the east. The next morning before dawn, a partially eclipsed moon was about to set in the west with Saturn just above it. Superstitious sailors probably took this as an ominous sign for the voyage. It may be why Ortega left port before May 3rd to avoid losing half the crew.

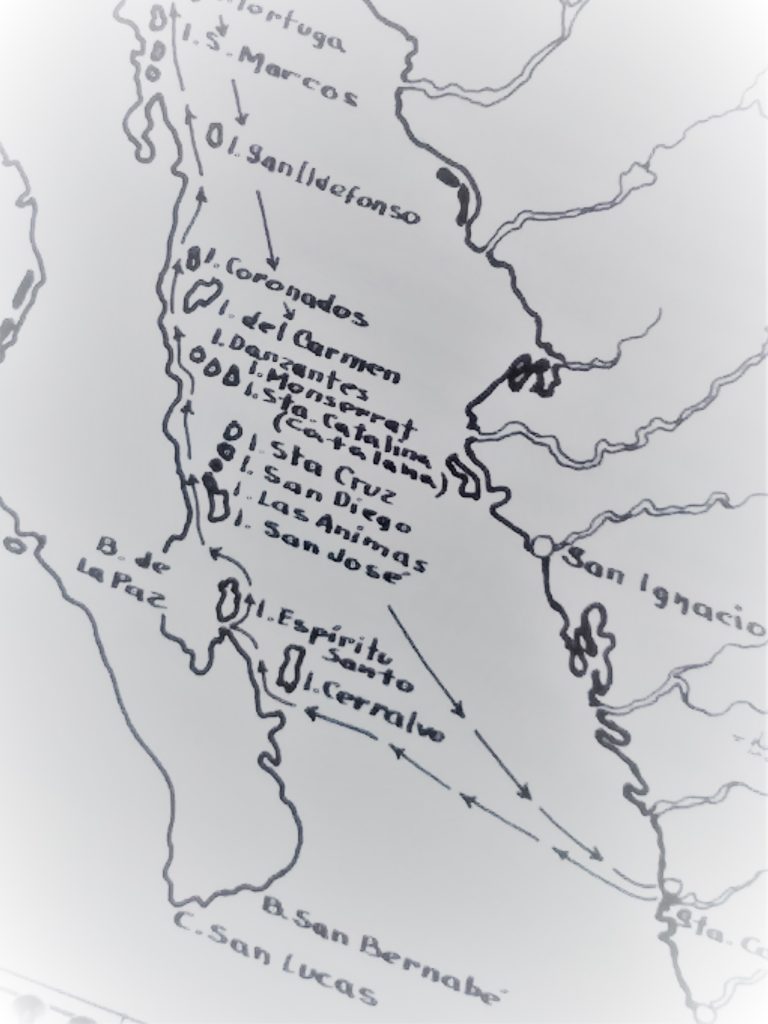

To honor the Viceroy, Ortega renamed the island Isla Cerralvo. The record says they continued the voyage and touched the coast of California where they met numerous “tame and friendly Indians.” If they continued the voyage by going west across the bay, they landed somewhere along the coast of El Sargento and La Ventana.

Weighing anchor, they sailed south to the tip of the peninsula. Indians came out on rafts to trade animal skins, pearls, and fish for cuchillos (knives). One of the sailors who went ashore lost his way back to the ship. He crossed paths with an Indian woman who took him to her home, a circle of rocks to block the wind. She fed the tired sailor fish and gave him a straw mat to sleep on, and a deerskin to stay warm. Several Indians took turns singing to him throughout the night. Sailing back north, Ortega looked for pearl beds along the shores of Cerralvo, Espiritu Santo, and the Bay of La Paz before returning to the continente (mainland).

*****

On Ortega’s second voyage to the Bay of La Paz, he was welcomed by Bacarí, the Pericú cacique (chief), then he sailed north again for several days, but contrary winds forced him back to La Paz. Upon his return, he learned that Bacarí’s son had been killed in a battle with the Guaycura. Runners had already been sent to inform other Pericú bands of the funeral ceremonies. Ortega remained several more days to mourn with his hosts and witness the funeral customs before returning to the mainland.

*****

Yrag whistled a sharp chip chip chip, to the crested red bird atop a tall cactus with branching arms raised to the sky. It cocked its head, and then flew in the direction of the mountains. Desert birds had started seeking shelter in anticipation of a tormenta (storm). Yrag understood the signs and knew it was time to take the mariscos (seafood) they had gathered and move to higher ground.

The small band took their few possesions, animal skins for warmth, weapons for hunting and protection, and bags woven of agave fiber for gathering food, and followed Ykceb up a winding trail. They crossed an arroyo, and climbed to a cluster of cuevas (caves) where they took refuge. Along the way, Yrret gathered the hierbas (herbs) she would need to make a poultice for injuries. Someone always seemed to need patching up after moving camp. At their new camp, she would sing a song to the children to prepare them for the coming storm.

Yrag looked back at the bay and did a double take. He saw a giant raft at the south end of the island. He watched as it floated north past the island. It would fall to Evets and Onnamre to run the news of its arrival through the Cunimniici to other groups of the Pericú nation. A strong, cold north wind began to blow. Yrag shivered. “I made the right decision to move camp to the caves,” he thought to himself.

*****

Ortega’s third and final voyage began on January 11, 1636. A favorable wind again carried the ship across the Gulf in two days. On January 13, the Madre Luisa entered the bay opposite Isla Cerralvo, and sailed north past the promontory opposite the island. The ship’s master advised Ortega to anchor for the night near la entrada (the entrance) to the Bay of La Paz. Al atardecer (At dusk), a cold, north wind began to blow and grew stronger during the night.

The next morning calamity struck. The ship’s scribe recorded that “a cable broke and dragged the anchor, the viento y olas (wind and waves) increased so that we were hurled against the shore where the frigate broke up.” Everyone survived, but the disaster left them marooned. There was no chance of being rescued.

By some milagro (miracle) the storm tossed most of the wood and supplies high on the shore. The crew retrieved the wreckage except for gunpowder and arcabuzes (harquebuses — small-caliber long guns operated by a matchlock). Ortega “… set about building a smaller sailing vessel, utilizing planks from the frigate,” the first sailing vessel built in the Californias.

Forty-six days later, with the smaller vessel completed, they launched and soon entered La Paz Bay. After replenishing their water and firewood, they anchored off the northern end of Cerralvo to explore for pearl beds. They sailed north, and Ortega discovered and named several more islands. He met with Guaycuras, and later claimed he learned their language. They traded for pearls before sailing back to the mainland.

*****

Further Reading:

León-Portilla (1973) Voyages of Francisco de Ortega

Anibal Lopez (2013) Evocaciones del Olvido (Reminders of a Forgotten Past – Rock Art of the Cape Region) English translation by Tom Spradley

Fujita & Munoz (2014) Prehistoric Settlement Patterns / La Paz and the Cacachilas

Rebman & Roberts (2012 – third edition) Baja California Plant Field Guide

Cuclo, July 2018, Ortega’s Diving Bell