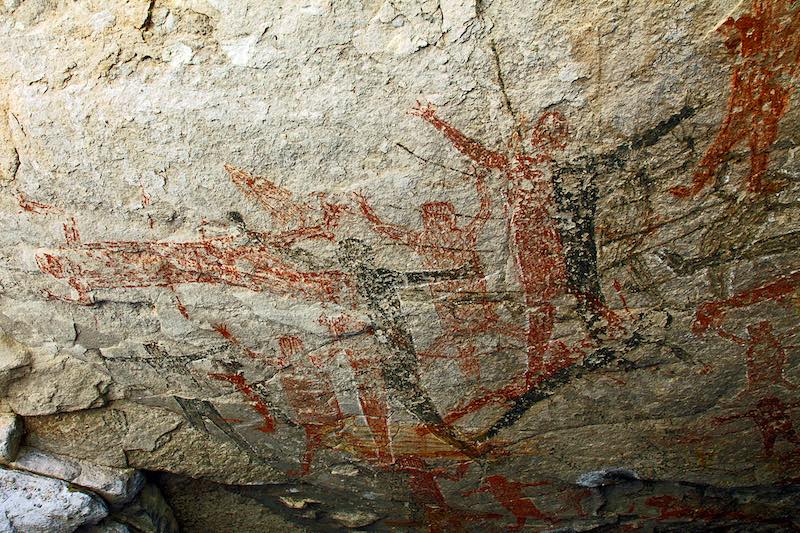

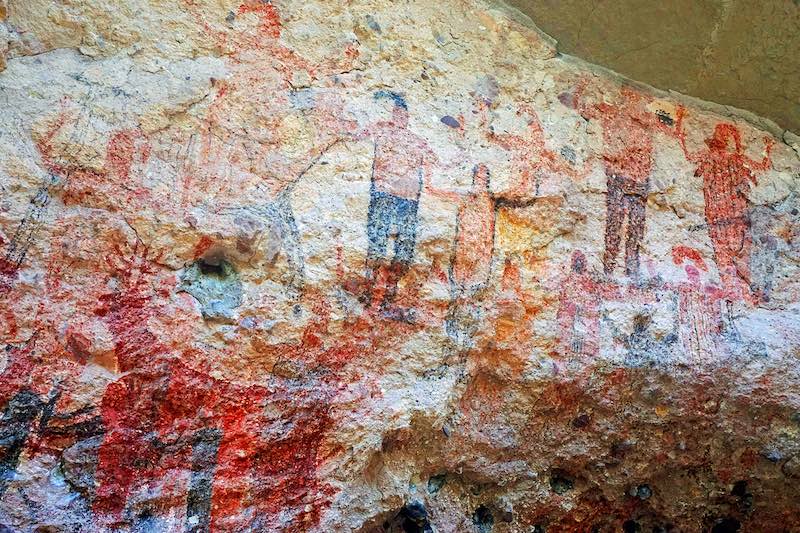

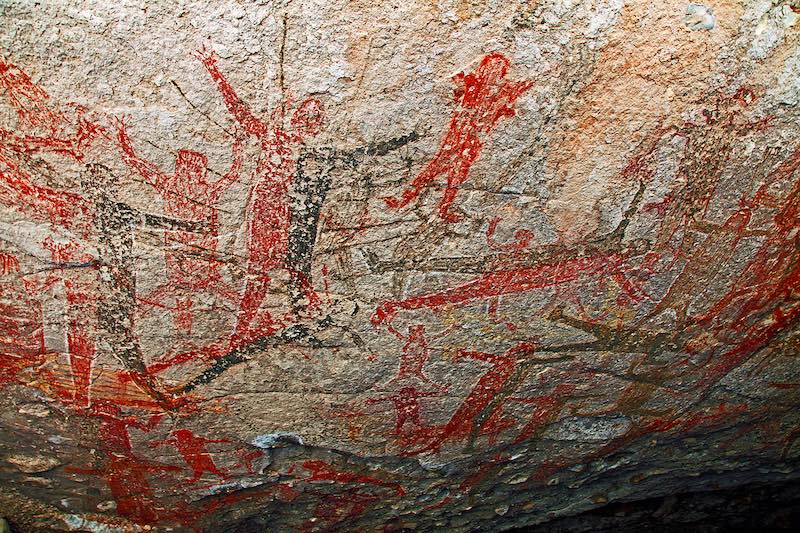

Jesuit Padre Joseph Maxiáno Rotheax gazed in surprise and wonder at the ceiling and back wall of the underside of the huge cliff. Staring back at him were a series of life-sized or larger than life-sized human figures standing with arms outstretched, feet wide apart. They were virtually neckless. The heads of many were decorated with several forms of headdress. Most of the figures were neatly split down the middle—one side painted in reddish pigment; the other in black. Some were depicted as having been shot with one or more arrows.

In addition to these apparitions, the cave contained simple but lifelike representations of mammals, birds and sea life. Based on evidence of extensive overpainting and faded pigments, Rotheax assumed the drawings were of great age.

Rotheax’s visit to this painted cave in the Sierra de San Francisco mountains of central Baja took place on an unknown date in the late 1760s, shortly before all Jesuit missionaries to the peninsula were recalled when the order was expelled from Spain. He had heard from Cochimi natives he served in San Ignacio of many caves reputedly painted by a race of giants who had migrated to the region from the north centuries earlier. Since many of the paintings are 20-30 feet above the floors of these cliff overhangs, known in Spanish as respaldos, the Cochimi believed that they could only have been created by giant artists.

His native informants claimed their people had nothing to do with the drawings; that, as far as was known, they were there before the Cochimi came to the region. They had no idea what they meant or how they were made.

Francisco Javier Clavigero, in his 1789 Historia de la Antigua o Baja California, was the first to describe the painted rock-shelters. He assumed that the pigment used was made from minerals found in the volcanic Las Tres Virgenes region. Clavigero noted that the colors had remained permanent through many centuries without being substantially degraded by air or water. Believing the pictures and dress did not belong to the stone-age natives living the region when the Spanish arrived in 1535, he suggested they depicted earlier inhabitants.

Little more was heard about the Baja murals for years. Other reports and studies followed in fits and starts, but the great Baja murals—now known to decorate thousands of respaldos throughout all of central Baja—made little impression on the public.

That would wait until the 1940s when famed mystery novelist Erle Stanley Gardner, creator of Perry Mason, made a hobby of Baja exploration. In 1962, after learning of the existence of the murals, he traveled by helicopter to the tiny village of San Francisco in the heart of the Sierra of that name and visited a group of four caves on foot and photographed five others from the air. When he saw the size and character of the artwork, he realized he was viewing a major archeological treasure. Gardner had interested archeologist Clement Meighan in accompanying him to explore the caves. The resulting scholarly papers and Gardner’s popular writing, including a sensational spread in Life Magazine and his book, The Hidden Heart of Mexico, put the murals on the map.

Gardner was so interested in the murals that he also flew by helicopter deep into the Sierra de Guadalupe northwest of Mulegé to explore a cave known as San Borjitas.

Author’s Note: I wish I had visited San Borjitas by helicopter. The trip in our guide’s 1988 Ford Bronco took three hours of jouncing over 30 km of boulder-strewn arroyos, of fording streams and of traversing six primitive ranchos. The climb up to the respaldo took about 30 minutes and would be classed moderate in difficulty. But, it was worth it! The cave contains over 80 monos—human figures.

Carbon-dated to be as much as 7,500 years old, the San Borjitas paintings are believed to be the oldest on the continent, and they are also some of the most impressive in Baja—the most awe-inspiring murals on the peninsula that can be visited in a day trip.

Author’s Note: A cave named La Palmarita, located northeast of San Ignacio, may be accessed in a day. Located 20 km off Highway 1 on a road that ranges from good to poor, the cave is about an hour-and-a half climb on a trail of moderate difficulty. Although the paintings it contains are not as extensive as those of San Borjitas, it’s much easier to visit. The trip can be organized by one of several outfitters in San Ignacio.

In the ’90s, explorer Harry Crosby logged over a thousand miles in the saddle through Baja’s topographically challenging middle section to interview isolated ranchers and, in doing so, discover more amazing prehistoric art and cave paintings. His gorgeously illustrated book, The Cave Paintings of Baja California: Discovering the Great Murals of an Unknown People (1998), documents the expeditions that revealed over 200 previously undiscovered rock art sites.

In 1993, the Sierra de San Francisco was placed on UNESCO’s World Heritage List. The scale of the paintings and the sensitive rendering of the artwork are unmatched on this continent. Parallels are often made between the works and the Paleolithic cave paintings of Spain and France created over 30,000 years ago by our Cro-Magnon ancestors.

The Baja murals are much younger, of course, but, despite efforts to plumb the mysteries of the paintings, their creators and the reasons for their creations remain elusive.

If interested in visiting cave murals: Salvador Castro Drew, 615-161-4985, operates out of Mulegé and can arrange trips of any duration to San Borjitas. He has 25-years of experience and speaks English. For a more in-depth experience, or to visit La Palmarita, Sea Kayak Adventures operates tours in the Sierra de San Francisco area. Contact rachel@seakayakadventures.com.

For more detailed information about the great murals of Baja, read “The Cave Paintings of Baja California,” by Harry W. Crosby. More information is also available here.