Since the arrival of the Spaniards in 1519, Mexico has gone through several major political iterations. But La Paz and the Peninsula have, in addition, had their own peculiar brushes with international politics. First, some early history.

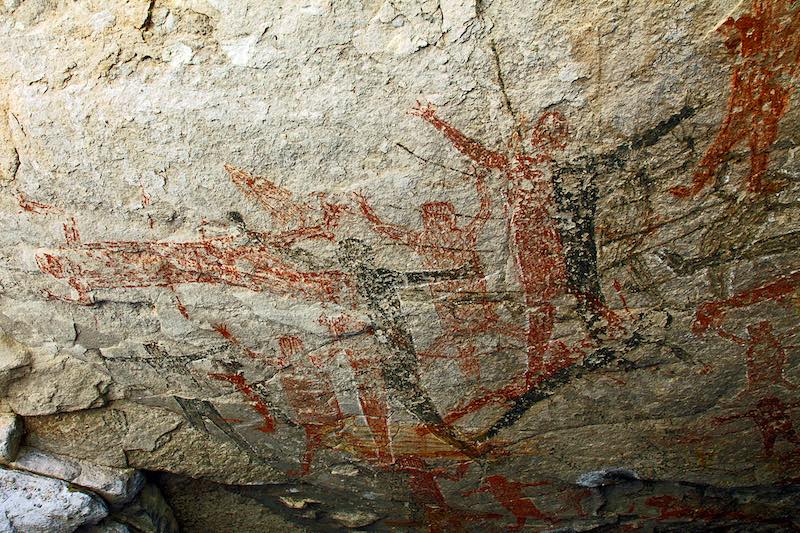

La Paz Bay was “discovered” in 1533 by Spaniard Fortun Ximenez, but efforts to establish a colony were thwarted by natives who killed him and his 21 crew members. Hernán Cortez arrived in 1535 after successfully subduing the mainland and named the Bay “Santa Cruz.” But his attempt to gain a foothold on the wild Baja peninsula also came to naught. His colony failed in a few years.

Fast forward to 1596 when the Spanish finally made a go of it. A successful colony was founded by Sebastian Vizcaíno and given the name “La Paz.” “New Spain,” as the country was known, held forth until 1821 when, after a protracted struggle (1810-21), the sovereign Republic of Mexico was established with the signing of the Treaty of Córdoba.

In 1861, however, conservative elements fought for the return of a monarchy. The French helped make it happen. France invaded and put monarch Maximillian I on a throne. The U.S. during this period, of course, was embroiled in the Civil War and didn’t have resources to help Mexican liberals keep the French out.

But, at the end of the war, the U.S. actively opposed Maximilian’s regime. France withdrew its support in 1867, monarchist-rule collapsed, Maximilian was executed, and the republic was restored.

Continue reading “The Invasion of La Paz by an American Filibuster” →