In 1940, author John Steinbeck took a breather from writing fiction—he had just published Grapes of Wrath (1939)—and ventured on a six-week, 4,000-mile expedition down the Pacific Coast of Baja and into and up what is now more commonly called the Gulf of California. Steinbeck and long-time marine biologist friend Ed Ricketts leased the Western Flyer, a 76-foot sardine boat out of Monterey.

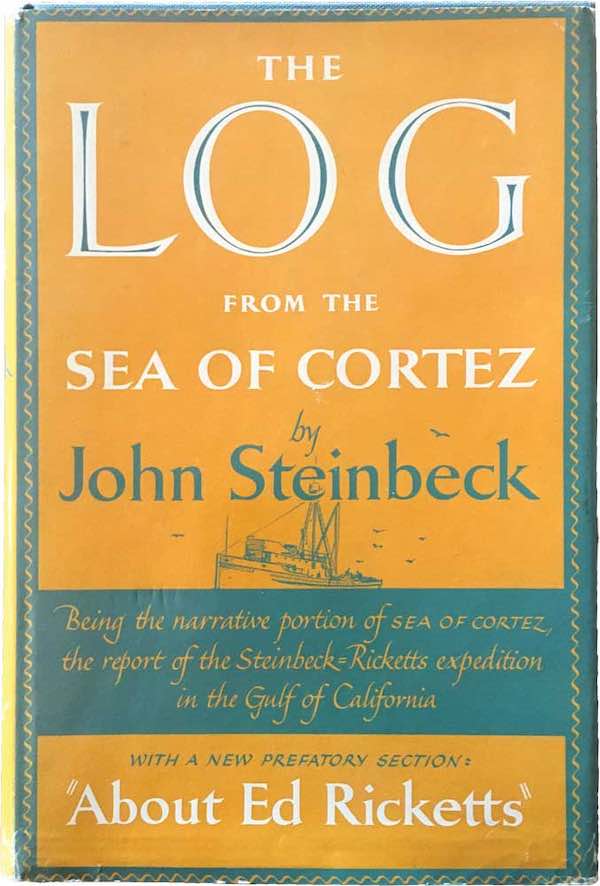

The result was a work of non-fiction, The Sea of Cortez (1941)—a 600-page pioneering treatise focusing on the intertidal or shoreline (littoral) ecology of Baja. Steinbeck published The Log from the Sea of Cortez, a more accessible preface to the much larger work, in 1951.

Here, in this two-part article, we focus not on marine invertebrates, but Steinbeck’s philosophical musings and observations of Baja in this pre-WWII era.

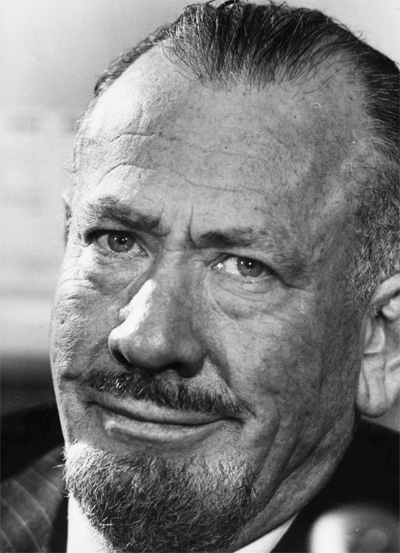

Pulitzer-prize winning author John Steinbeck had a “thing” about Baja. Born in Salinas, CA, in 1902, the Salinas Valley, Monterey and the Pacific Coast—about 25 miles distant—would serve as settings for some of his best fiction. The location also sparked a deep and abiding interest in marine biology, enhanced as a young man after he took a course on general zoology in 1923.

His first major success came in 1935 with Tortilla Flat, stories about Monterey’s paisanos. Two of his best known and most powerful novels followed: Of Mice and Men (1937) and Grapes of Wrath (1939). And there were dozens more including Cannery Row (1945) and his monumental East of Eden (1952), the saga of the Salinas Valley and his own family history.

In 1940, however, Steinbeck took a breather from fiction and ventured on a six-week, 4,000-mile expedition down the Pacific Coast of Baja and into and up what is now more commonly called the Gulf of California. Steinbeck and long-time marine biologist friend Ed Ricketts leased the Western Flyer, a 76-foot sardine boat out of Monterey.

The result was a work of non-fiction, The Sea of Cortez (1941)—a 600-page pioneering treatise focusing on the intertidal or shoreline (littoral) ecology of Baja. Steinbeck published The Log from the Sea of Cortez, a more accessible preface to the much larger work, in 1951.

This exciting day-by-day account of their expedition combines science, philosophy and high-spirited adventure—providing a much fuller picture of Steinbeck and his beliefs about humans and the world. In addition, the book provides interesting and valuable insights into the history of Baja just prior to the outbreak of World War II.

At the time, reviewer Lewis Gannett, New York Herald Tribune, said: “This is at once the record of a serious biological expedition and the impact of a biologist and novelist upon each other’s minds. The best of Steinbeck is in it.”

In his Introduction, Steinbeck scholar Richard Astro said: “In his best fiction, Steinbeck worked out the conflict between primitivism and progress, between his own view of the world and that of Ricketts—both of which were based…on a scientific view of life organized around the concept of wholeness which is as spiritual as it is biological.”

So, the book is more than a record of exploration. In its pages, Steinbeck frequently waxes philosophical:

We have looked into the tide pools and seen the little animals feeding and reproducing and killing for food. We name them and…arrive at some conclusion about their habits…but we do not objectively observe our own species as a species…. When it seems that men may be kinder to men, that wars may not come again, we completely ignore the record of our own species. If we used the same smug observation on ourselves as we do on hermit crabs, we would be forced to say…’It is one diagnostic trait of Homo Sapiens that groups of individuals are periodically infected with feverish nervousness which causes the individual to turn on and destroy…his own kind.

Details in the book about the myriad, strange and wondrous creatures of the littoral are certainly of scientific interest. The sex life of the sea cucumber, for example, may be a turn on for marine biologists—and certainly for the sea cucumber. But it was Steinbeck’s observations of the Baja of that pre-World War II era that I found to be most compelling.

The Western Flyer departed Monterey on March 11, 1940, and, after a short stop in San Diego for supplies, motored continuously, reaching Cabo St. Lucas the night of March 17.

On that first morning we cleaned ourselves well and shaved while we waited for the Mexican officials to come out and give us the right to land. They were late in coming, for they had to find their official uniforms, and they too had to shave…. It was noon before the well-dressed men in their sun helmets came down on the beach and were rowed out to us. They were armed with the .45-caliber automatics which everywhere in Mexico designate officials.

When Steinbeck and his mates went ashore, they found that the “sad little town” of San Lucas had recently been wrecked in a single night by a vicious winter storm. Water from the pounding surf had driven past the houses, and streets of the village of a few hundred souls had become raging rivers.

We stopped in front of a mournful cantina where morose young men hung about waiting for something to happen. They had waited for a long time—several generations—for something to happen, these good-looking young men. In their eyes was a hopelessness.

The expedition left the next day after intensive specimen collection on the beach that today is the glitzy Cabo San Lucas Malecón and motored around the cape and into the waters of the Gulf. No mention is made of San Jose. The focus, instead, was on reaching a planned collection stop at Pulmo Reef. But the marine life they found there was certainly no more interesting than Steinbeck’s observations of the natives they encountered:

…the little canoe put off and came along side. In it were two men and a woman, very ragged, their old clothes patched with the tatters of older clothes…. They sat in the canoe holding to the side of the Western Flyer, and they held their greasy blankets carefully over their noses and mouths to protect themselves from us. So much evil the white man had brought to their ancestors: his breath was poisonous…. Where he set down his colonies the indigenous people withered and died…

Then, as now, Pulmo Reef teamed with marine life.

Clinging to the coral, growing on it, burrowing into it, was a teeming fauna. Every piece…skittered and pulsed with life—little crabs and worms and snails. One small piece of coral might conceal 30 or 40 species, and the colors of the reef were electric.

Next stop for the expedition was to be Point Lobos on Espíritu Santo Island at the mouth of La Paz Bay. The Western Flyer entered La Ventana Bay in the late afternoon. No mention was made of the sleepy fishing villages of La Ventana or El Sargento nestled at the apex of the bay, but, as the boat motored past Cerralvo Island, the crew encountered a phenomenon known to all to inhabit the region. El Norte began to howl, forcing them to forego Point Lobos on the eastern side of Espíritu Santo and to shelter under Pescadero Point.

That night, finally in calm waters, Steinbeck wrote:

Nights at anchor in the gulf are quiet and strange. The water is smooth, almost solid, and the dew is so heavy that the decks are soaked. The little waves rasp on the shell beaches with a hissing sound, and all about in the darkness the fishes jump and splash.

The next day, March 20, the crew sailed from shelter under Pescadero and again crossed the San Lorenzo Channel to collect specimens on the south side of the island.

It was a very short run. There were many manta rays cruising slowly near the surface, with only the tips of their ‘wings’ protruding above the water. They seemed to hover, and when we approached too near, they disappeared into the blue depths.

Continue reading Part Two. Steinbeck is enchanted by La Paz, and, as the expedition continues its journey north, the crew of the Western Flyer spends time with “Our Lady of Loreto” and encounters a huge Japanese shrimping fleet.

Learn more about Lorin’s two recent books—The 13: Ashi-niswi (2018) and Tales from The Warming (2017)—at www.lorinwords.com.